What is Honey Process Coffee?

Honey processed coffee is a fairly new term, originating in the last 10 years or so. Honey process coffees originated in Costa Rica as a new, experimental form of processing to cut down on water consumption.

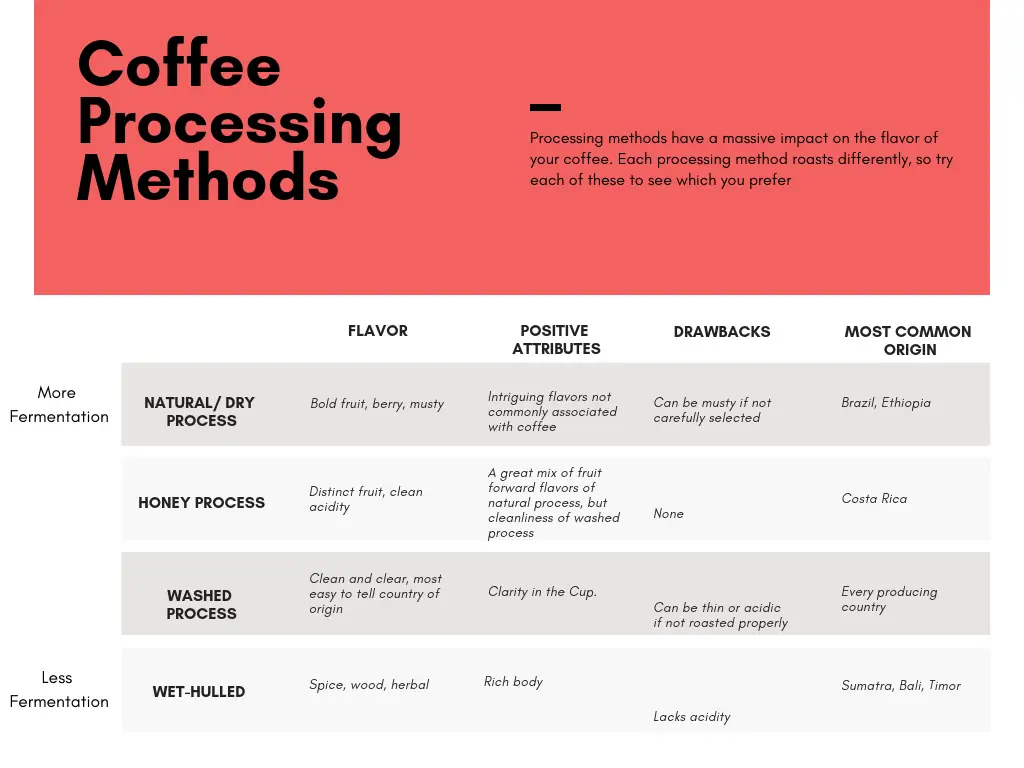

The honey process is a hybrid of the washed process, standard in most specialty coffee, and the dry process, which is common in Brazil and Ethiopia.

In any honey processed coffee, the skin and pulp of the coffee cherry is mechanically removed with a jet of water. What’s left is called the mucilage. This has also historically been called the ‘honey’ of the coffee fruit because of its sticky, gummy texture.

The coffee seeds are left to ferment with this sticky mucilage still on. Depending on how quickly and to what degree the seeds are fermented, producers will give different designations, such as white honey, yellow honey, red honey, and black honey. The darker colors are meant to indicate that the coffee seed has spent more time fermenting in the mucilage.

With honey processed coffees, you taste much of the cleanliness and clarity of a washed process coffee, but still get the unique fruit and berry sweetness imparted by the seeds extended fermentation. While honey processing didn’t begin as a way to impart unique flavors, it’s become increasingly popular both in Costa Rica and in surrounding Central American countries.

Types of Honey Process Coffee

White Honey

White Honey Process coffee is fermented for the least amount of time. It is typically dried out in the open sun, where it is flipped often to keep a cap on enzymatic and bacterial activity. Shortly after drying, the mucilage is washed away and the coffee bean is dried for export.

White Honey Process coffees are the closest to washed process coffees. They still have fermented and sweet fruit flavors, though those flavors are more of a slight accent than a full statement.

Yellow Honey

Yellow Honey Process coffees take White Honey Process just a bit further. They are still fermented quickly, but typically spend around a week drying. While honey processed beans are fermenting in their mucilage, they are constantly tended to with turning and agitating. This is why honey process coffees can cost a fair deal more than other processing methods.

Red Honey

Red Honey Process coffees are the perfect middle ground between the washed and natural processes. I think of Red Honey Process coffee as the center of the spectrum.

Red Honey processed coffees spend between two and three weeks drying. Within such a long time-frame, there are often overcast days and sunny days, so the natural variation in weather will slow or speed fermentation accordingly. As you move farther down the spectrum of honey processed coffees, it becomes increasingly important that the farmer or mill operator is skilled and diligent in turning the coffee beans. Without constant attention, the coffee can turn sour, moldy, and over-fermented.

However, because most honey process coffees we’ll see as home roasters have been pre-selected by specialty coffee buyers, you’re essentially guaranteed that you’re getting something from a highly skilled and experienced farmer.

Black Honey

Black Honey Processed coffee is the most fermented coffee on the honey process spectrum. This tastes the closest to full natural process coffee.

Because Black Honey Process coffee is fermented for so long, at least two weeks and perhaps more depending on weather, it usually costs the most. This is because of the attention and care that goes into turning the seeds as they ferment.

With the extra fermentation, richer fruit flavors are present in the finished cup of coffee. Black honey processed coffees tend to be on the wilder side in terms of flavor, giving off full sweetness and body, while also imparting some fermented, musty flavors.

Honey Process History

Honey processing became popular in Costa Rica in 2008 after a massive earthquake struck the country and caused water shortages. Previously, most coffee mills in Costa Rica had used the washed-process method, which produces clean and bright flavors, but is water-intensive.

Several farmers, most famously the Chacon family at Las Lajas mill, began to look outside of their country for other, less water-reliant methods of processing coffee beans. They found that producers in both Brazil and Africa had developed methods that worked much better with drier climates and didn’t depend on so much water usage.

Only a small amount of water is used to remove the skin and pulp of the coffee cherry. What’s left is the sticky mucilage. This is then dried out in the sun for several days and removed after fermentation with a small amount of water. There’s no need to fill giant tubs and vats with water, making honey processed coffees an attractive option for coffee mills.

While honey processing became popular in Costa Rica, it’s spreading to other countries in Central America, both because of the reduced water and because demand in consumer countries has risen a great deal.

How to Roast Honey Processed Coffees

Because honey process coffees vary in their degree of fermentation, you’ll want to take that time into consideration when roasting.

White and yellow honey processed coffees are the closest to washed process coffees, and while I don’t treat them with as much heat up front as I normally would with a dense washed process, I begin with more heat than a natural or black honey process coffee.

The idea in roasting the lighter end of the honey process spectrum is that you’re working with something that has mostly clean flavors. By roasting more aggressively, you’re bringing out more acidity and clean, bright taste.

As you move farther down the honey process spectrum toward red and black honey process coffees, slow the roast down a bit. You’re working with coffees that are similar to natural process coffees, so their sugars caramelize much faster than in washed process coffees.

If you were to roast a washed process coffee and a black honey process coffee for the same time in the same manner, the black honey process coffee would appear darker because more of its sugars would have broken down and caramelized. This is because of how much enzymatic activity has already occured with the additional fermentation. More sugars have been made available by yeasts and bacterias. Delicious.

I personally never like to roast dark with honey process coffees, just because they are so well tended to and have such interesting flavors. I want my roast to bring out as much sweetness as possible and leave a pleasant amount of acidity. Stay on the lighter end of the roasting spectrum. You’ll be rewarded with the crisp acidity of a Central, but with a hint of fruit reminiscent of Ethiopian naturals. To me, it’s a perfect blend.

Other Experimental Processing Methods

Since the explosion of honey process coffees, farmers and millers around the world have been experimenting with different processing methods, both for flavor and to account for environmental factors.

Raisin Process

Raisin process coffees require a tremendous amount of care, as the coffee cherries are left to dry on the tree before they are picked. Rather than drying after being picked, as in natural processing, the drying on the tree allows the coffee seed to interact with its fruit without fermentation.

Raisin process coffee isn’t widely available, though that should be changing in the coming years. A recent lot in 2017 Cup of Excellence had a Brazilian raisin process coffee go for over $120/pound. With that kind of money coming in, we can expect to see more farmers attempt raisin process in the future!

Repassed Process

Repassed process coffees are growing in popularity. Similar to the experimental raisin process, repassed coffees have partially dried on the tree. When the coffee cherries are floated in large vats for the washed process, repassed cherries float to the top. They are then selected from among the defects and are processed separately. Those who tout repassed coffee claim its sweeter and milder because of the additional contact with fermenting fruit.

Kopi Luwak

Also known as cat poop coffee, or even monkey poop coffee, Kopi Luwak is partially processed in the digestive tract of a civet, which is neither a cat nor a monkey: it’s a civet. The civet eats the coffee cherry and digests the pulp and mucilage, leaving the coffee seed in tact. The digestive enzymes subtly alter the flavor of the coffee bean in a similar way that natural processing and fermentation do.

Roast Some Honey Process!

Give honey processed coffee a shot and let me know what you think in the comments below!

If you’re looking to find some honey processed coffees, check out my list of importers and distributors of green coffee for home roasters. For more information on selecting green coffee, take a look at some of my other articles.

2 comments

Like!! I blog frequently and I really thank you for your content. The article has truly peaked my interest.

Thank you so much for the kind words!